There’s been a lot of name-calling lately. Fascist, Marxist, Communist, etc. These are labels that purport to assign a character, ideology, and ethos to a person. But as Tony Kushner said in Angels in America through the character, Roy Cohn, “…labels refer to one thing and one thing only; where the person so identified fits in the food chain, in the pecking order.” In other words, labels define a status—a power relationship between you and them.

Name-calling is meant to reduce a person’s status, to make them lesser, different, other, non-human. And that makes it much easier to justify behavior that oppresses—or worse—that person. Names can also elevate a person’s status—Queen, King, GOAT. This justifies behavior that exalts that person, such that we might be less inclined to criticize or challenge. In his book, Impro, Keith Johnstone describes the status games we play, and how pervasive they are on stage and IRL. I employ his status games in my acting classes quite often, and to good effect! It was a great way to enter into the idea of character. We use characters as labels, too. “He’s such a Romeo!” These labels are almost instant ways of establishing a relationship with someone, evoking a whole set of attitudes, prejudices and assumptions that allow you to assess threat or opportunity. You know who they are, you’ll have a good idea what they’ll do, and you’ll be prepared to act—fight, feed, flee, fuck. Acting is predicting. But what is it about these labels that provides us with information we can act upon?

When I was working on my first book on acting (Acting: An Introduction to the Art and Craft of Playing. Pearson. 2007), I put together Johnstone’s work with Northrup Frye’s work, Anatomy of Criticism. It seems to me that certain archetypes are generally associated with certain tasks and actions. This is both innate and learned. We are wired to predict threat/opportunity via the Mirror Neurons System. And we are taught—by art and experience—to recognize the intention of behaviors, particularly as embodied by general types of people.

For example, most of us can readily recognize the intent of a hand raised in welcome, versus a hand raised to strike. A classic middle school tease is to raise the hand swiftly “as if” to strike and then bring the hand down gently on the head “as if” straightening the hair. “Made you flinch!”1

Over time, via experience and exposure to stories, images, etc. we begin to associate certain behaviors with certain types of people. It’s a handy short-hand to help us predict what might happen. So, when we are followed by a large person on a dark street, our MNs may kick in with dire predictions. Over millennia, these types become enshrined in folklore, myths and tales and become archetypes. There’s a lot of literature on archetypes and I encourage anyone to read up on them. For my purposes, I want to focus on just four because these tend to show up in most forms of theater, in movies, and almost any narrative art form.

This is an excerpt from my book that sums it up.

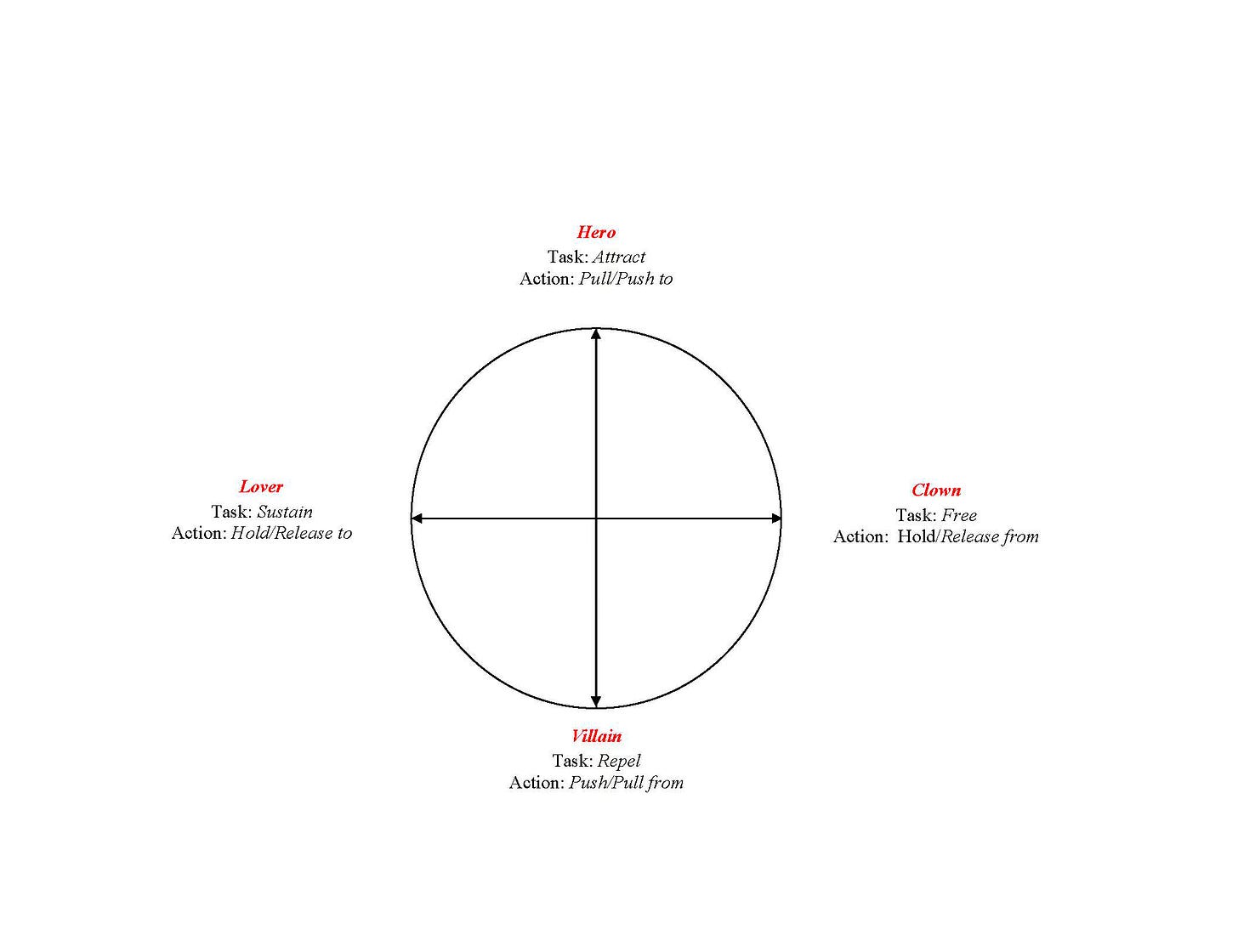

A type is simply a very basic character—that is, recognizable patterns and pathways of energy. Over time, these patterns have been given different names, depending upon the historical/social/political milieu. But these character patterns are evident in many (if not all) cultures and times. Artists employ these patterns all the time, re-creating and re-imagining them for their own uses. Types function as signs for an audience, creating expectation, anticipation and suspense regarding what will happen. There are numerous sources for you to research regarding a character type (Commedia dell’ Arte, Kabuki and Noh theater, contemporary movies, to name a few), but a convenient way to map types, and therefore to help you locate yours, is using our mandala with four points: Hero, Villain, Lover, and Clown.

The Hero represents constructive, creative energy. The Villain represents destructive, chaotic energy. The Lover represents connective energy and the clown represents disruptive energy. As you may guess, these types correspond to the four basic tasks. The Hero’s task is to attract—bring forth an answer, unite the troops, inspire to act, build a city, save the day. The Hero’s fundamental actions (how the Hero accomplishes the task) are to pull/push to. The Villain’s task is to repel—to drive apart an alliance, to break the peace, to destroy the world! Their fundamental actions are to push/pull from. The Lover’s task is to sustain—to keep love and hope alive, to heal wounds, to maintain the peace, and urge others to “let go.” Their fundamental actions are to hold/release to. The clown’s task is to free and keep at bay—dispel tensions, burst bubbles, escape the rules; their fundamental actions are to release/hold from. Most types can be boiled down to one of these four essences and certainly down to some combination or other of two, three or even all four (although a combination of all four would be more like a full human being rather than a limited type).

Recognize anyone?

In the public arena, we are currently witnessing certain political players being “cast” as hero or villain, depending on who is doing the casting. But it must be pointed out that one person is casting an entire political party as “the enemy within.”

Character matters. A person’s character is conferred upon someone by others based on patterns of behaviors that are predictable. We say someone has a good character when we can RELY on them to do what is conducive to the collective welfare of society. Someone is described as having a bad character when we cannot rely on them to behave in predictable ways and that often their behavior is disruptive to the welfare of society. But none of us live in a monolithic society. Rather, we have constructed societies for ourselves, based on our beliefs about what constitutes welfare. We see this not just in the current US political campaign, but across the world in geo-political conflicts of various natures. One person’s hero is another person’s villain.

But we cannot reduce each other to types or characters, nor label one another in ways that diminish the fullness of our humanity. Each one of us is more than any character ever written, and each of us has an inherent dignity and worth that must be recognized. Cognition is a higher order function. It takes energy to overcome our instinctual and learned predictions, and to see that what appears to be a threat, may actually be an opportunity. That’s what makes us human.

Because I’m a natural actor, I was a sucker for these games—really status games of domination and submission. At least, that’s what I tell myself. It’s comforting.